Maybe Programs Can Learn Functional Programming

I’ve been thinking for a while now about how to teach a machine to program. Most machine learning and statistics is very structured, even the nonparametric stuff. But we continue to make the same assumptions (like pretending everything’s linear) because we have to. When we try to drop those assumptions, we go to super general models, like trees/forests or deep nets. These are great, but still mostly work under the assumption that all of our data is vectors. For example, plugging a word model into an general-purpose model will typically use something like one-hot encoding with super high dimensions, or word vectors (the super cool CRFs).

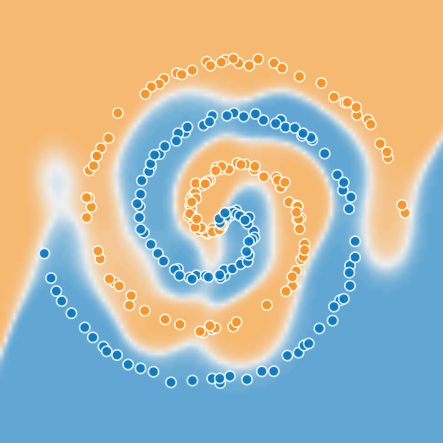

It’s certainly not how I think about problem solving or pattern matching, and for general purpose representations, it just seems inefficient. With enough data and a big enough model we can teach a model to interpolate anything, but extrapolation is still a challenge. Go to the tensorflow playground and try to model the swiss role distribution.

Even a really good model isn’t going to extrapolate well further from the origin than the training set. By comparison, it’s trivial for us as people to identify the geometric rule actually used to label the data. Putting that intuition to math, it’s something like \(sin(k r + \theta) > 0\). That rule is much more compact than the one learned by the tensorflow model, and likely would extrapolate far better. Learning algorithms have shown themselves to be really effective at learning useful representations and composing them together, so why not learn to compose more useful functions? Let’s teach a computer to program!

The first obvious question is what a simple minimal programming environment for a machine would be. What kind of language should it use? We could go with the most basic building blocks of reads, writes, and memory, like the NTM paper, but that’s seems like the assembly language of program induction. I can’t even write in assembly! There are a few other approaches out there, but they all still seem very low level, and all imperative. It occurred to me that with pure functions, I get to be dumb. I don’t have to think about state, and programming is like putting legos together! Just make sure the type signatures fit and then compose stuff!

The challenge here is choice. With structured data, as opposed to numerical vectors, we can’t combine everything in nice smooth, optimizable ways. We have to choose between different blocks we might put together. Learnable choice is tough since it’s not differentiable, but that is exactly the sort of problem reinforcement learning deals with. It turns out there are pretty general approaches to propagate gradients on random graphs like this.

So I think it could work. I’ve spent the bunch of weekends and evenings setting out to learn if a simple model of composing the programming version of lego blocks can learn anything interesting. The first part is deciding what building blocks allow lots of interesting programs to be expressed concisely (hint: lambda calculus is awesome). The next piece is to represent the AST and function composition in a learnable form. After that, I’d like to see how to extend beyond simple languages into more expressive ones with user defined data types and fancier type systems until I’m teaching a machine to program like I do. I’m going to try to document the development as I go.

(Note: It turned out super hard, but very interesting. It was kinda a failure, so I didn’t do a full writeup, but here are some notes about it)